It’s not easy to live as a bird in winter. Discover how birds survive extreme cold using smart adaptations, behaviors, and resilience.

How Birds Manage in Cold Winter

Have you ever stopped to think about the tiny creatures flitting around your backyard during a harsh winter day? It’s not easy to live as a bird. And how birds manage in cold winter is a story of incredible resilience, clever adaptations, and sheer determination. As someone who’s spent countless mornings watching chickadees and cardinals brave the snow from my kitchen window, I’ve always been fascinated by their survival tactics. In this article, we’ll dive deep into the world of avian winter survival, exploring everything from physiological tricks to behavioral strategies that help these feathered friends make it through the toughest months of the year.

Winter poses a multitude of challenges for birds. The dropping temperatures, scarce food sources, and relentless winds can turn even the most vibrant ecosystem into a frozen wasteland. Yet, birds have evolved over millennia to cope with these conditions. We’ll look at how small birds survive cold winters, the adaptations that allow them to endure, and even ways we humans can lend a hand. Along the way, I’ll weave in some personal observations and insights to make this feel less like a textbook and more like a cozy chat by the fire.

The Harsh Realities of Winter for Birds

First off, let’s set the scene. Imagine being a bird in the dead of winter. Your body temperature hovers around 105°F – much higher than a human’s – which means you’re constantly burning energy just to stay warm. However, food is harder to find because insects have vanished, seeds are buried under snow, and berries are long gone. In addition, shorter daylight hours give you less time to forage. It’s a perfect storm of energy demands and limited resources.

For many species, like the black-capped chickadee or the American goldfinch, winter survival hinges on balancing this equation. According to experts, birds lose heat rapidly in cold weather, and without enough calories, they can succumb quickly. For example, a small bird might need to eat up to 20% of its body weight daily just to maintain its core temperature. That’s like a 150-pound person chowing down on 30 pounds of food every day!

Moreover, weather extremes amplify these issues. A sudden blizzard can cover food sources, while icy rains can soak feathers, reducing their insulating power. Birds in northern climates, such as those in Canada or the northern U.S., face even steeper odds. Studies show that winter mortality rates can spike during particularly severe seasons, affecting population dynamics come spring.

But it’s not all doom and gloom. Birds have developed an arsenal of strategies to combat these threats. Transitioning to how they adapt physiologically, let’s explore the inner workings that keep them alive.

Physiological Adaptations: Nature’s Built-In Survival Kit

Birds aren’t just winging it when winter hits; their bodies are equipped with remarkable physiological tools. One key adaptation is their feathers, which act like a high-tech winter coat. By fluffing them up – a process called piloerection – birds trap pockets of warm air close to their skin. This creates an insulating layer that can be as effective as the best down jacket on the market.

In fact, some birds grow extra feathers in the fall, increasing their plumage by up to 30%. Take the common redpoll, for instance. These hardy finches add thousands of additional feathers to bulk up against the Arctic chill. Furthermore, their feathers are often oiled with a special preen gland secretion, making them water-resistant and even more effective at retaining heat.

Another fascinating trick is regulated hypothermia, or torpor. Many small birds, like hummingbirds or kinglets, can lower their body temperature by 10-20°F at night to conserve energy. It’s like hitting a pause button on their metabolism. However, this isn’t true hibernation; they can snap out of it quickly if needed. For songbirds surviving winter, this can mean the difference between life and death during long, cold nights.

Birds also have a unique circulatory system that helps. Their legs and feet are designed with a counter-current heat exchange mechanism. Warm blood flowing down the legs transfers heat to colder blood coming back up, minimizing heat loss. That’s why you see birds standing on one leg – they’re tucking the other into their warm feathers to preserve energy.

Additionally, birds pack on fat reserves in the fall. This subcutaneous fat acts as both insulation and fuel. A bird might double its body weight in preparation, drawing on these stores when food is scarce. But managing this fat is a delicate balance; too much weight hinders flight, while too little leads to starvation.

Shivering is another tool in their kit. Unlike humans, birds can shiver intensely for hours, generating heat through muscle contractions. Their high metabolic rate – up to five times that of mammals their size – allows this without exhausting them completely.

These adaptations aren’t uniform across species. Migratory birds might rely less on them since they head south, but resident birds like the northern cardinal have honed these traits to perfection. Speaking of which, let’s shift to behavioral strategies that complement these physical ones.

Behavioral Strategies: Smart Moves for Winter Survival

Physiology is only half the story; behavior plays a crucial role in how birds survive extreme cold. One common tactic is communal roosting. Birds like starlings or wrens huddle together in tree cavities or dense shrubs, sharing body heat. I once spotted a group of bluebirds crammed into an old woodpecker hole during a snowstorm – it’s like a feathered slumber party that boosts survival rates.

Foraging habits change too. In winter, birds become opportunistic eaters. Insectivores switch to seeds or berries, while others cache food in advance. Chickadees, for example, hide thousands of seeds in the fall, relying on their impressive spatial memory to retrieve them later. This caching behavior can account for up to 50% of their winter diet.

Moreover, birds adjust their activity patterns. They forage intensely during the warmest parts of the day, often right after dawn, to maximize calorie intake. On bitterly cold days, they might minimize movement altogether, perching in sheltered spots to conserve energy.

Shelter-seeking is vital. Evergreen trees provide windbreaks and cover from predators, while man-made structures like barns or under eaves offer refuge. Some birds even burrow into snow banks for insulation – the ptarmigan does this masterfully, creating igloo-like dens.

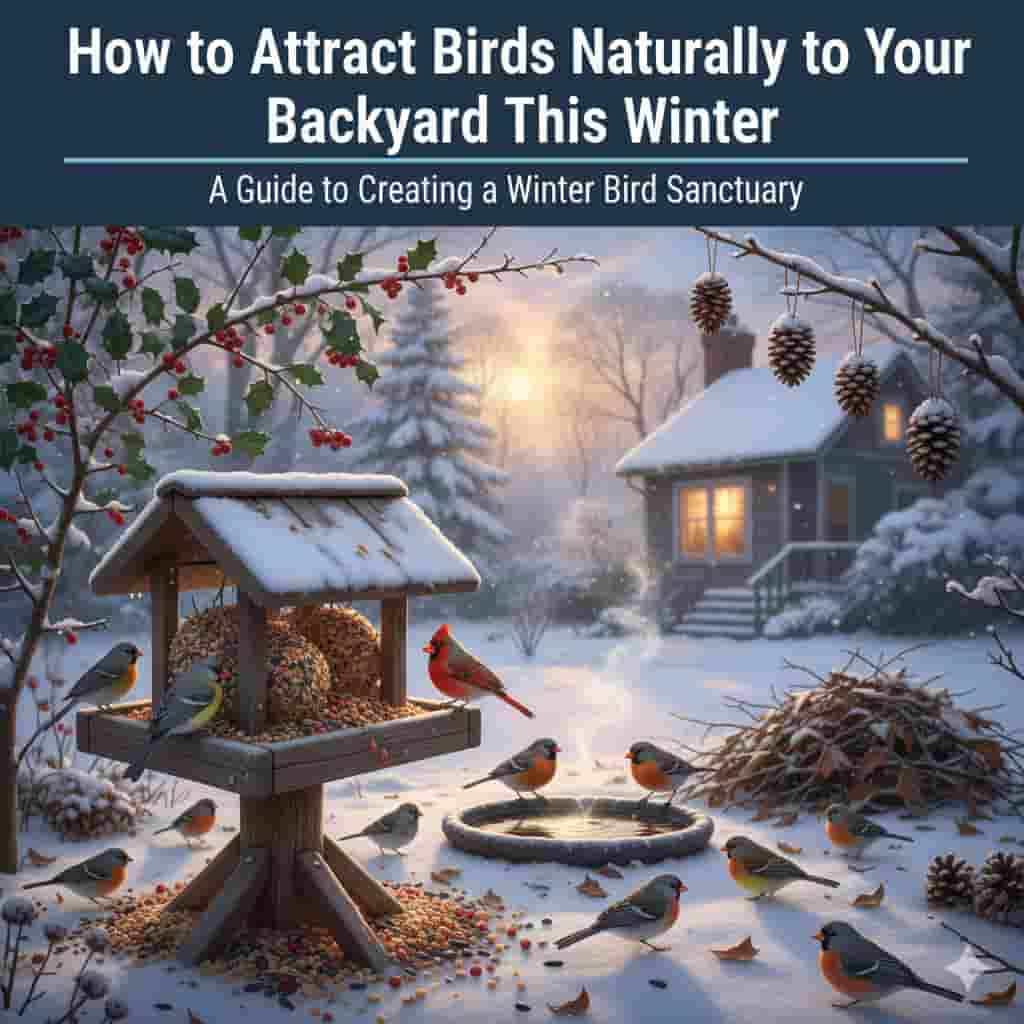

Water access is another challenge. Frozen ponds mean birds must find open sources or eat snow, which costs energy to melt. That’s why heated birdbaths can be a lifesaver, but more on human help later.

Predator avoidance adds complexity. With fewer leaves for cover, birds are more exposed, so they form mixed-species flocks for better vigilance. A junco might team up with titmice, benefiting from collective eyes spotting hawks.

These behaviors vary by region. In urban areas, birds exploit human resources, like feeders or heated vents. In rural forests, they rely more on natural caches. Either way, flexibility is key to bird winter adaptations.

Migration vs. Residency: Choosing the Path to Survival

Not all birds tough it out; many migrate to warmer climes. But why do some stay? It boils down to energy costs versus benefits. Migration is risky – long flights, unfamiliar territories, predators – but it guarantees milder weather and abundant food.

For residents, staying means adapting to local conditions. Species like the tufted titmouse have evolved to handle cold, with traits favoring survival over the energy drain of migration. However, climate change is shifting these dynamics. Warmer winters might encourage more birds to stay put, altering ecosystems.

Take the Canada goose. Once strictly migratory, many now overwinter in cities thanks to open water and grass. This “short-stopping” reduces migration risks but can lead to overpopulation.

In contrast, long-distance migrants like warblers face dual challenges: surviving winter in the tropics and the journey back. Habitat loss in wintering grounds exacerbates this.

Understanding these choices helps us appreciate the diversity of strategies. For birds that stay, winter is a test of endurance; for migrants, it’s about strategic relocation.

Species Spotlights: How Different Birds Tackle Winter

Let’s get specific with some examples. The black-capped chickadee is a winter warrior. These plucky birds use torpor, caching, and social flocks to thrive. Their “chick-a-dee-dee” calls even convey predator info, aiding group survival.

The northern cardinal, with its bright red plumage, stands out against snow. Males defend territories year-round, relying on thickets for cover and seeds for food. Females fluff up dramatically, looking like feathered puffballs.

Owls, like the great horned owl, hunt at night when prey is active. Their dense feathers and large size help retain heat, and they often take over nests in protected spots.

Small birds like the golden-crowned kinglet are marvels. Weighing less than a nickel, they huddle in groups and enter deep torpor, surviving temps down to -40°F.

Waterbirds face unique issues. Ducks like mallards have waterproof feathers and can dive for food under ice. They cluster on open water, using group warmth.

Each species has its niche, showcasing evolution’s creativity in bird survival in cold weather.

Human Impacts and How We Can Help

Humans play a big role in bird winter survival. Urban sprawl reduces habitats, but we can mitigate this. Providing feeders with high-energy foods like suet or black oil sunflower seeds helps. Just remember to clean them to prevent disease.

Planting native shrubs offers natural food and shelter. Berry-producing plants like holly or serviceberry are goldmines. Additionally, leaving leaf litter provides insect foraging grounds.

Avoid pesticides; they deplete food chains. And consider window decals to prevent collisions – a major winter hazard when birds seek warmth near buildings.

Climate change worsens winters with erratic weather, so conservation efforts matter. Supporting organizations like the Audubon Society can make a difference. For more on helping birds, check out this resource from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology: All About Birds – How to Help Birds in Winter.

The Bigger Picture: Climate Change and Future Challenges

Climate change is reshaping how birds manage cold winters. Warmer averages might seem beneficial, but they bring unpredictability – late freezes killing early migrants or mismatched food availability.

Drier winters in some areas reduce water sources, while increased storms destroy habitats. Species like the snow bunting, adapted to extreme cold, may face range shifts.

Research shows migratory timing is advancing, but not always in sync with food peaks. This “phenological mismatch” threatens populations.

Conservationists advocate for protected corridors and habitat restoration. By understanding these shifts, we can better support birds

Wrapping Up: Lessons from Our Feathered Friends

It’s not easy to live as a bird, especially in cold winter. Yet, through ingenious adaptations, behaviors, and sheer grit, they persevere. From fluffing feathers to caching seeds, these strategies inspire awe.

As we face our own challenges, perhaps we can learn from them – adaptability, community, and preparation. Next time you see a bird in the snow, take a moment to appreciate its journey.

People Also Ask

It’s not easy to live as a bird in winter because extreme cold, limited food sources, and shorter daylight hours increase energy demands while reducing survival opportunities.

Birds survive cold winters by fluffing their feathers for insulation, increasing body fat, shivering to generate heat, and using specialized circulatory systems to reduce heat loss.

Birds rely on dense winter plumage, torpor to lower body temperature at night, high metabolic rates, and counter-current heat exchange in their legs.

During winter, birds switch diets, cache food in advance, forage more efficiently, and rely on seeds, berries, and human-provided feeders.

Migration helps birds avoid harsh winter conditions by moving to warmer regions with more abundant food, despite the risks involved in long-distance travel.

Species like chickadees, cardinals, owls, and kinglets are well adapted to winter due to their insulation, social behaviors, and energy-saving strategies.

Birds huddle together in sheltered spaces to share body heat, significantly reducing energy loss during cold winter nights.

Climate change causes unpredictable winters, food mismatches, habitat loss, and altered migration patterns, making it even harder for birds to survive.

Humans can help by providing clean feeders, high-energy food, fresh water, native plants, and safe shelter while avoiding pesticides.

Birds teach us resilience, adaptability, preparation, and cooperation — proving that even in harsh conditions, survival is possible with smart strategies.